Chandler Museum expands Japanese American exhibit

Chandler Museum has added new elements to its signature Japanese American exhibit, giving visitors a deeper narrative perspective on the history of the Gila River Relocation Camp during World War II.

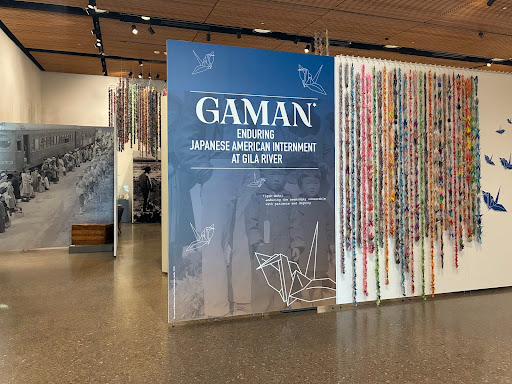

The exhibit, Gaman: Enduring Japanese American Internment at Gila River, originally opened in 2018 but its run was cut short by the 2020 pandemic.

Jody Crago, museum manager of Chandler Museum, said he decided to bring back Gaman after five years of the public asking him about its return.

The new additions since the last showing

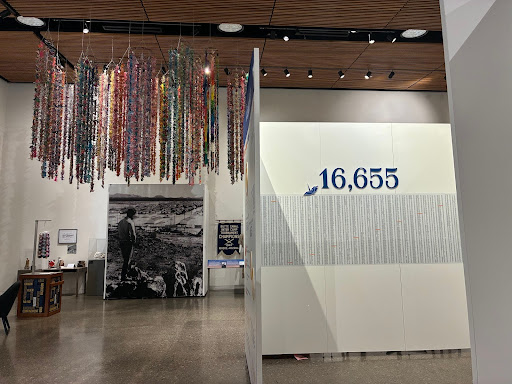

Among the new features in the current exhibit is the 16,655 paper cranes hanging from above.

“The ones above us represent the internees in the Gila River camp,” he said. All of them used to be displayed in the front of the exhibit, but they have been moved up to the ceiling.

Three months before the first version of Gaman opened, Crago said they had received 24,000 cranes from all over the country. Some of those cranes now hang on the wall at the exhibit’s main entrance.

Another addition was donated by a nurse who worked in the relocation camp. In one of the hospitals, an internee’s mother was so thankful for the good care received that she gave a handmade paper rice doll to one of the nurses there, Crago said.

Many of the quote panels from the previous version of Gaman have been rearranged and expanded upon. “We took some of those quotes and we did a little bit more family research,” he said, “so we could talk about incarceration, life during incarceration, and then what happened to them beyond that.”

Life in the camps for internees

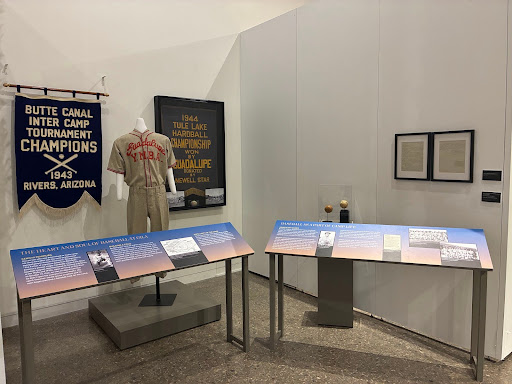

One of them is a handwritten letter from Kenichi Zenimura, a semi-pro baseball player who created the baseball team at Gila River.

“Baseball was like a lifeline to so many boys that were part of the camp,” Crago said. “They actually played some of the other camps that had all-star teams as well.”

According to Crago, there was pushback for a follow-up game with the Tucson High School baseball team. Many residents there didn’t want the Gila River team to come because they were Japanese American internees, he said.

In the letter, Zenimura writes to the baseball coach of Tucson High School after finding out the game was canceled due to backlash from residents. Visitors can read the letter on the information panel, where there is a clearer transcription version of it.

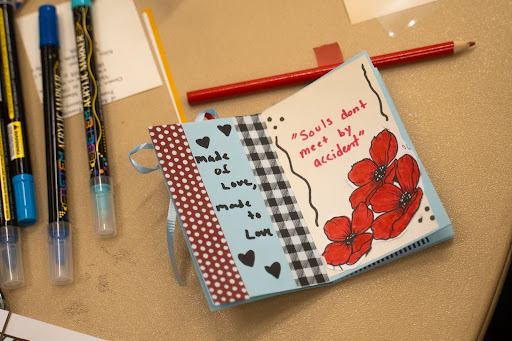

“While they no longer followed a dusk-to-dawn schedule, their time in camps provided opportunities for recreation and pastimes,” Crago said. There is one section of the exhibit dedicated to showing some of the arts and crafts made by internees.

The history and ethical implications of the internment

Near the beginning of the exhibit is the “I Am an American” photograph taken by renowned dust bowl and WWII photographer Dorothea Lange.

According to Crago, the man who owned that grocery store in San Francisco was eventually relocated to the Gila River camp.

“After Pearl Harbor, there was a ton of fear,” said Paul Hietter, chair of social sciences at Mesa Community College. “There was fear of an attack on the Pacific Coast, possibly another attack in Hawaii.”

The Japanese population in Arizona wasn’t large, he said, so most Japanese Americans from California would have been relocated to the camps in Arizona.

“From the tribal perspective, they never wanted the camp on their land,” Crago said, “but the federal government still wanted it there.”

Within the exhibit is a printed wall showing Japanese Americans being evacuated from their homes and forced onto trains. “There’s a sort of trauma that comes from it,” he said in reference to the image. “If your country turns around and does this to you, are you really the same American as the person next to you?”

According to Hietter, “Fear causes people to do things that they wouldn’t normally do under normal circumstances.” Oftentimes, these are actions that are unjust, he said.

What is the purpose of the exhibit?

“The story needs to be told as many times as possible so that the same mistakes aren’t made again,” Crago said. “The folks lived with ‘gaman,’ unbelievable strength and unity despite this unlivable situation.”

Crago said he hopes that visitors will be inspired by Gaman to explore other media sources, such as books and films, to gain a deeper understanding of the history surrounding the relocation camps and their aftermath.

“We’re a city museum funded by taxpayer dollars,” he said. “We’re not here to force an agenda, but we are here to lay the facts out.”

Even after Gaman ends next year on Jan. 26, 2026, Crago said he will always remain dedicated to telling the story of the Gila River relocation camp through future exhibits.

“I’ve researched this topic for years now, maybe even a decade,” he said. “We’re in a fraction of time where I’m proud that we’re having this conversation.”