Chandler Museum debuts exhibit featuring Japanese American internee letters through photographer’s lens

Chandler Museum showcases a local photographer’s works for the first time in a new exhibit to reveal what everyday items Japanese American internees across the U.S. requested from outside the relocation camps.

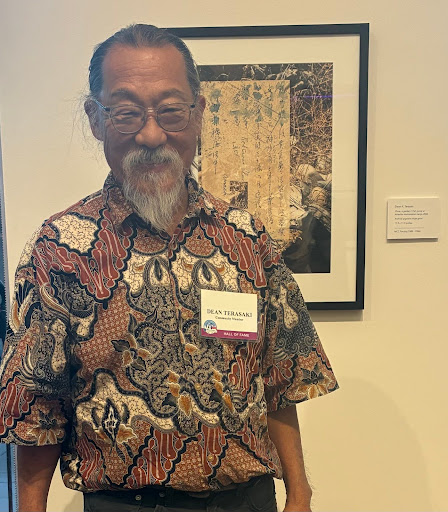

Echoes Unearthed is a collaborative show with co-president of Eye Lounge and Phoenix-based photographer Dean Terasaki.

Terasaki will also speak on Nov. 8 at the Chandler Public Library event “Our Stories Speaker Series: Echoes from a Box of Photos.”

This is the very first time that Chandler Museum is showcasing any of Terasaki’s work, according to Kristine Clark, curator of Chandler Museum.

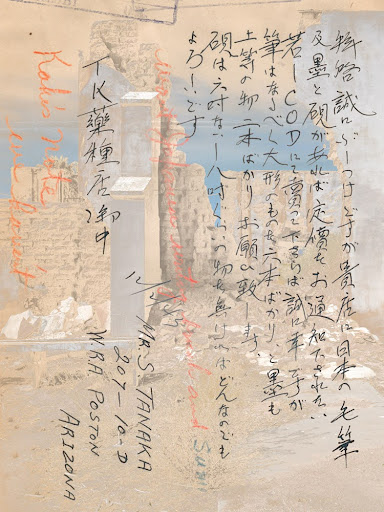

“It’s a bridge between art and history,” she said. Each piece is a meticulous layering of handwritten letters from internees and photographs of their respective origin location.

The two sheer kimonos on display were specifically made by Terasaki and his wife for the exhibit, Clark said. She wanted to bring some of his photomontages to the museum so that it could be in conversation with their similar exhibit Gaman.

History on the photomontages

Terasaki was a Mesa Community College professor from 1985 to 1986, and said he has been making photomontages like these since graduate school.

Terasaki said the letters came from all ten of the camps as well as a couple of federal detention facilities. He has been to eight of the ten major camps, but has not visited Gila River since the 1990s.

“Most of them are national historic sites,” he said. “Some of them there’s just a single monument and a couple have scattered evidence that there was a camp there.”

During World War II, Japanese American internees were often last in line for medicine and other rationed necessities because they were prisoners.

“The TK Pharmacy was a lifeline for them,” Terasaki said. “There was a level of trust there that they would get what they asked for.”

They were one of the very few Japanese American owned businesses that were allowed to operate during the war, Clark said.

Terasaki’s uncles ran the TK Pharmacy out of Denver, Colorado. He believes one of them, Todd “Tak” Utaka, held onto the letters and never told anyone about them before his passing.

In 2012, the building was purchased by a new set of owners who uncovered the letters during renovation. Later on they ended up being uploaded to Densho, an online public domain archive.

By getting permission from Densho, Terasaki was able to take the scanned copy of the letters and layer them with his own photographs of the landscape from where the letter was originally sent.

A deeper look at the letters within the photomontages

Most of the letters are written in Japanese kanji and have captions with paraphrased translations. However, there is one from Mazanar that is in English for visitors to read from.

“It’s like this marriage of the past and the present,” Clark said, “seeing this layering of the past with the letter and also the present with the land.”

She points out that none of the letters are written as rants about life in the camp, but rather simple requests for essential items.

“There’s people that were asking for astringent and this request for Japanese medicine,” she said.

A few of the letters are requests for other items, such as hair dye, ink, and paint brushes. “Medicine is more of a necessity than [hair] dye, but it’s that attempt to maintain a sense of dignity,” she said.

Some of the letters also ask for sake, a traditional Japanese rice wine served as the choice of drink for many internees during times of celebration.

“The idea of the sake is that there were still high school graduations,” Terasaki said. “There were still kids being born, there were still weddings—there were funerals where you would toast to the deceased.”

When visitors view the photomontages, they can get a sense of what “gaman” meant to the Japanese American internees. Gaman is a Japanese term meaning enduring the unimaginable with dignity and grace.

“Nothing can be done, but you put your best foot forward and carry on,” Terasaki said.

As a sansei, Terasaki is a third generation Japanese American. Because his family lived on the other side of the line of exclusion, they were not relocated to any of the camps.

How the experience as an internee reflects back onto later generations

Kathy Nakagawa is an associate professor emeritus of Asian Pacific American studies at the School of Social Transformation from ASU. Both of her parents were relocated to different internment camps and shared their experiences with her.

Nakagawa, owner of Baseline Flowers, said her father and his family were sent to Poston, forcing them to give up their farming land and all their crops. They had immigrated to Arizona just before World War II.

However, Japanese American families with farms living north of the line of exclusion were allowed to sponsor out interned families to help gather their crops. One of those families chose to sponsor them.

After about a year of staying in the camp, Nakagawa said her father and grandfather were able to take advantage of that opportunity to leave the camp.

Her mother’s family was in California at the time and was eventually sent to Jerome, Arkansas. They felt betrayed by the U.S. and later moved back to Japan after the war, she said.

“Both my mom and dad graduated from high school while in the camps,” Nakagawa said. Eventually, her mother and her siblings returned to the United States.

She said she had grown accustomed to the Japanese phrase “Shikata ga nai,” which is a direct translation of “It cannot be helped.”

“It was as if something bad had happened in the past,” she remarked. “My parents would discuss their experiences if you asked them about it, but they didn’t bring it up often.”

Nakagawa recalled a story from her mother of when the FBI came to her home and began searching it without a warrant. Her maternal grandfather was a leader in the community and often targeted because of it, she said.

“She described how angry she felt about that,” Nakagawa said. In addition, her father told her about how poorly built the barracks were.

“When they arrived in Poston, they were given sacks filled with bales of straw,” she said. The sacks of straw were meant to be their mattresses.

“Because the barracks were erected so quickly, the wood was very green and dried out, allowing all the dust to come in,” she said.

According to her, many people didn’t want to talk about their experiences in camp due to a sense of shame. “Even though it wasn’t their fault that they were imprisoned, that feeling of shame was still present,” she said.

“This isn’t just a single story of my family’s experience,” Terasaki stated. “It’s the experience of the entire Japanese American community.”

Chandler Museum unveiled Echoes Unearthed on Oct. 21 and plans to keep it open until March 2026.

While some of Terasaki’s photomontages on display have already been seen by the public, they are also part of his ongoing collection titled Veiled Inscriptions.

With the museum’s exhibit Gaman running until late January, visitors can gain background context of Japanese American internment before visiting Echoes Unearthed.

The museum is located on 300 S. Chandler Village Drive, just outside of the Chandler Fashion Center mall area. Admission is free year round for all visitors.