Flint faces corrosion, corruption amid water crisis

Keith Whittemore

Mesa Legend

Problems in Flint, Mich. run deeper than its pipes. Concerns about lead and bacterial contamination in Flint’s water supply have been mounting since April 2014, when the city switched its water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to using water from the Flint River in an effort to cut costs. Since the change, residents of Flint have cited the color and smell of their water, as well as widespread health problems such as chemical burns and hair loss, as evidence of city mismanagement. Subsequent testing both of the water and of Flint residents has since confirmed high levels of lead in the water, as well as a possible Legionnaire’s disease outbreak. The likely cause of the contamination is the use of lead pipes combined with untreated Flint River water.

Problems in Flint, Mich. run deeper than its pipes. Concerns about lead and bacterial contamination in Flint’s water supply have been mounting since April 2014, when the city switched its water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to using water from the Flint River in an effort to cut costs. Since the change, residents of Flint have cited the color and smell of their water, as well as widespread health problems such as chemical burns and hair loss, as evidence of city mismanagement. Subsequent testing both of the water and of Flint residents has since confirmed high levels of lead in the water, as well as a possible Legionnaire’s disease outbreak. The likely cause of the contamination is the use of lead pipes combined with untreated Flint River water.

Lead pipes were common in municipal water systems built before the 1950s due to the low cost and malleability of the material. When exposed to untreated water, the pipes can be corroded and lead can leach into the water, causing serious health problems. At the time of the 2014 switch, a news release from the city of Flint claimed the water was safe. The city government more or less toed that line until January 2016, when Gov. Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency in Flint, although internal memos indicate that some officials were aware of problems as early as February 2015. On Feb. 10, 2016, the mayor of Flint and a local doctor were called to testify on the matter, and Snyder proposed $195 million in additional relief funds.

The ensuing media attention has state and federal officials looking for answers on how this happened and what can be done to solve it. According to professor Rod Golden of MCC’s sociology and African-American studies department, though, the ongoing issues in Flint are only symptoms of deeper cultural and political problems. Flint, like many other Midwestern cities, has been subjected to relentless urban decay caused by the loss of the region’s main economic powerhouse, the steel and automobile industries. Golden, who has had family throughout the so-called Rust Belt, grew up in Hyde Park, a historically diverse neighborhood in Chicago.

“You didn’t have to leave the city limits to go shopping, to participate in entertainment — everything was at your disposal, you never had to go without,” Golden said. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, however, the region languished as companies like General Motors – founded in Flint – moved their plants out of state to reduce labor costs. The result, Golden said, was devastating, particularly among vulnerable groups like African-Americans. “When you talk about the decline of the auto industry and the steel industry, you’re also talking about a decline in population, and a decline in talent that’s going elsewhere,” he said. The loss of manufacturing work in the area also entailed the decline of ancillary businesses like restaurants and cleaners, leading in turn to declining tax revenues to pay for public education and other services.

As an alternative to municipal bankruptcies, Michigan governors decided, beginning in 1988, to appoint unelected emergency managers to settle issues within troubled areas, many of which are predominantly poor and black — among them Flint. According to Michigan’s 2012 Local Financial Stability and Choice Act, emergency managers have authority over all local elected officials, including the mayor and City Council, and serve at the will of the governor. These managers can, among other things, hire or fire local government workers, modify or terminate union contracts (with state treasury approval), change local budgets, and sell city assets. “Democracy is suspended in the state of Michigan,” Golden said. “When you appoint an emergency manager, the mayor has no power, city council has no power, the school board has no power.”

The managers’ appointment has not gone unchallenged. John Conyers, a representative from Michigan’s 13th congressional district, sent a letter in 2011 to the Department of Justice, requesting an investigation of the situation, citing violations of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and Article 4 of the Constitution. In addition to concerns about the extent of the managers’ control, there have also been allegations of corruption and incompetence – best evidenced, some say, by Flint’s current water woes. “You’ve got folks in Flint who really had never done this sort of thing. They’d always gotten their water from Detroit, so they’d never had any experience with treating water,” MCC history professor Paul Hietter said. “They didn’t really have any idea what they were doing, and after they screwed things up, they covered it up.”

Because emergency managers are subject only to the governor, the only way they can be removed from office is by order of the governor or by impeachment for a crime. The problem, then, according to Golden, is that Flint residents are not voting effectively, or even at all. “Governor Snyder was re-elected. He put in emergency managers in his first term,” Golden said. “A lot of people in politics don’t respect (these populations) because they don’t vote,” he continued. “They’re not exercising their civic duty… because they don’t feel that their vote counts.” Hietter cited the same concern. “That’s really the biggest problem with poverty — it’s not having that voice,” he said. “They’re basically ignored. If this happens in Gilbert, Arizona, you think this gets ignored? There’s no way.”

Golden and Hietter also criticized the lack of coverage for the crisis in the media.

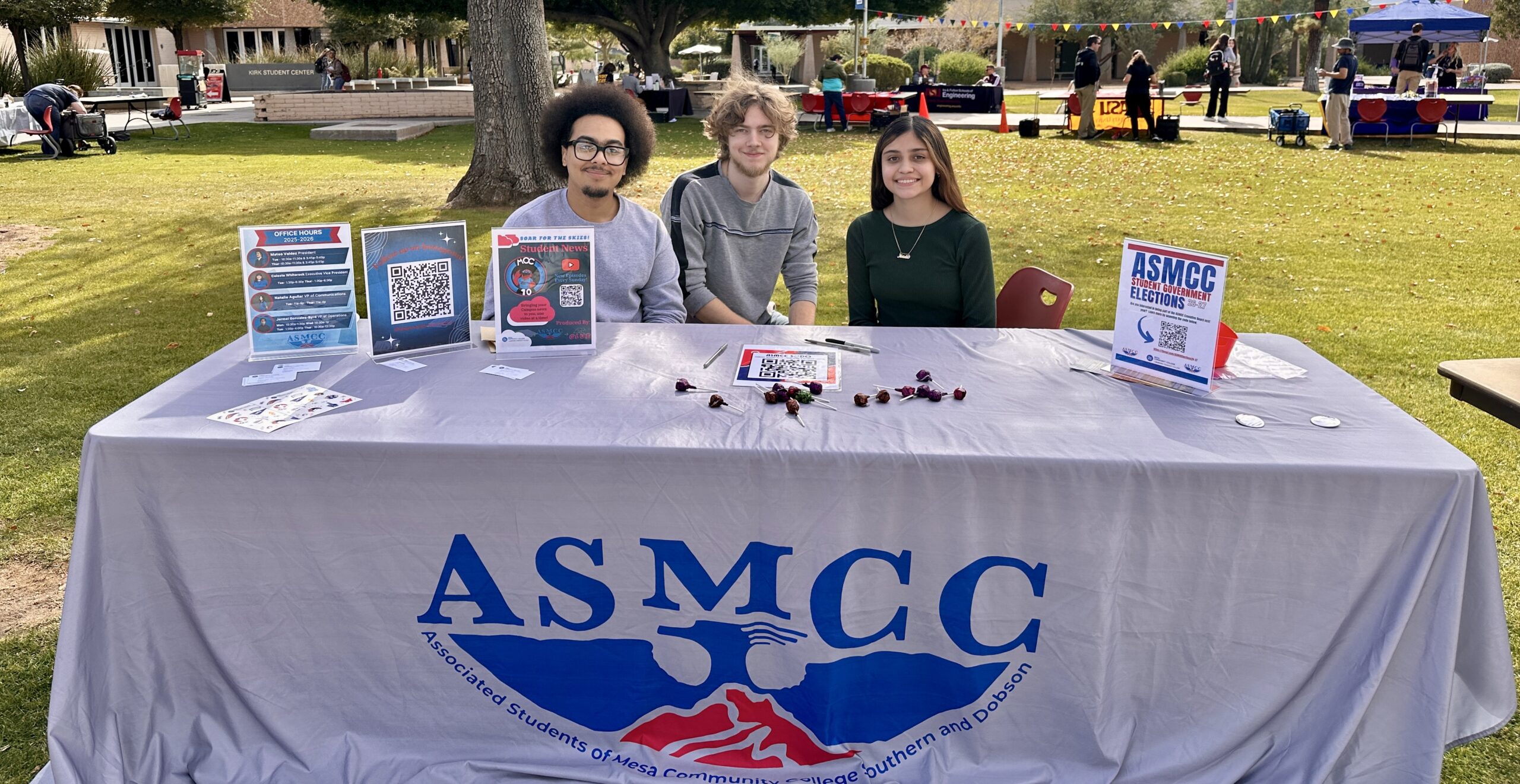

“The coverage is good now, but it sounds like it was pretty lacking back when all this started,” Hietter said. “Two years seems like an awful long time for this to be dragging out.” “The media has been very slow to report,” Golden said. “It’s not a state issue. It’s a human rights issue, a human rights violation.” Among the lessons to be learned, Hietter said, is that, if it can happen in Flint, it can happen anywhere. “You don’t realize how quickly things we take for granted — electricity, clean, safe water — it can go bad quickly. It’s amazing how fast it can turn bad,” he said. ASMCC and the Black Student Union will be taking donations of bottled water and hygiene products for Flint until the issue is resolved. For more information, contact Denise Campbell by e-mail at vpfa.asmcc@gmail.com.